Mots-clés

Publication

Extraits

“The term Permanent Revolution has its roots in Marxism; I have gleaned from it what I want for purposes of foregrounding prose experiment as crucial to those who identify as women; +, by extension, to proximate others on the ever widening scale of gender distribution. To recognize that gender minorities are – as are other diverse minorities – in a permanent state of emergency as concerns life + the expression of it is necessarily to reshape how we narrate as a species.” 1 1 Scott, Gail. Permanent Revolution. Book*hug, 2021, p. 5.

“Where there is no emergency, there is likely no real experiment.” 2 2 Permanent Revolution. p. 60.

“I was convinced, for example, that relative linear movement of plot did not correspond to the way we think, talk, live. I was looking for a relationship between my need to ‘explode’ language, syntax, in line with what I perceived as my fractured female being. I was also fascinated by how desire circulated through the masks that my women friends + I seemed to adopt in our various roles: mother, writer, militant, lover, friend. This seemed to preclude the development of unary female characters in prose, + consequently, of plot in any conventional sense.” 3 3 Permanent Revolution. pp. 95–96.

Biographie

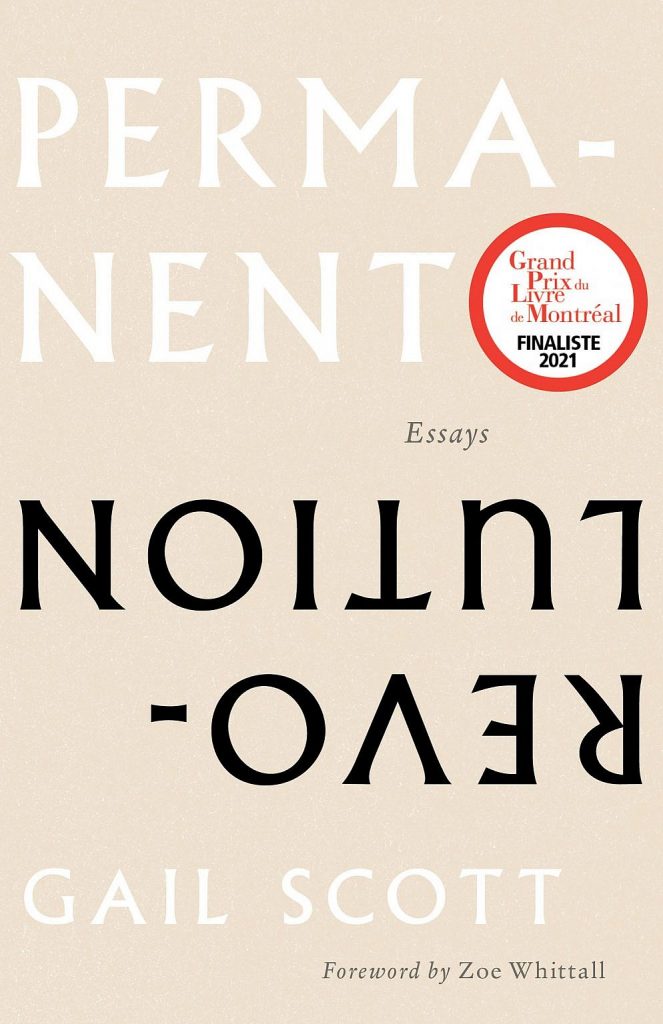

Montréal-based writer Gail Scott, born in 1945, grew up in a bilingual rural community in Eastern Ontario. She studied English and French literature before beginning her writing career as a journalist in 1967. During this time, she edited and co-founded multiple political and cultural small press publications; she subsequently taught journalism at Concordia University from 1980–1991. She has written four novels (Heroine, 1987 4 4 Scott, Gail. Heroine. Coach House, 1987. ; Main Brides, 1993 5 5 Scott, Gail. Main Brides: Against Ochre Pediment and Aztec Sky. Coach House, 1993 .; My Paris, 1999 6 6 Scott, Gail. My Paris: A Novel. Mercury, 1999. ; The Obituary, 2010 7 7 Scott, Gail. The Obituary. Coach House, 2010. ), the last of which was a finalist for Le Grand Prix du Livre de Montréal. She is also the author of a short story collection, two essay collections, and four English translations of French-Québécois novels, one of which (The Sailor’s Disquiet, 2000 8 8 Delisle, Michael. The Sailor’s Disquiet. Translated by Gail Scott, Mercury, 2000. ) was shortlisted for the 2001 Governor General’s Literary Awards. She co-authored La Théorie, un dimanche (1988) 9 9 Bersianik, Louky, et al. La théorie, un dimanche. Les Éditions du remue-ménage, 1988. , a fiction/théorie essay collection, and co-edited Biting the Error (2004) 10 10 Burger, Mary, et al., editors. Biting the Error: Writers Explore Narrative. Coach House, 2004. , a New Narrative anthology. 11 11 Moyes, Lianne, editor. “Brief Biography of Gail Scott.” Gail Scott: Essays on Her Works, Guernica, 2002, pp. 231–234.

Résumé

Permanent Revolution is an experimental essay collection that explores the connection between writing and socio-political issues. Scott uses an unconventional writing style 12 12 See the “Style & Aesthetics” section of this reader’s guide for more on Scott’s writing style. that allows her to raise questions without prescribing definitive answers. The first section of the book, “The Smell of Fish,” presents contemporary essays, mostly written in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic, that explore current and ongoing social upheavals in relation to Scott’s own writing and life. The second section takes its title from Scott’s 1989 essay collection, Spaces Like Stairs, and features a selection of essays revised for republication. These pieces, originally composed in the ‘70s and ‘80s, reflect on experimental writing in the context of the feminist and separatist Québécois movements of those years. In this way, Permanent Revolution presents two halves of one whole: halves separated by several decades but woven together by thematic threads and the backdrop of Montréal. The newer essays in the collection echo, recast, and develop ideas that first burgeoned in her earlier writing, while the revised older essays illuminate evolutions in Scott’s ever-shifting context and praxis.

Situer l’œuvre

Permanent Revolution is in conversation with queer New Narrative 13 13 See the glossary of this reader’s guide for an explanation of New Narrative. and Québécois feminist fiction/théorie, 14 14 See the glossary of this reader’s guide for an explanation of fiction/théorie. two movements concerned with the representation of minority subjects in writing. As Scott says, “both queer and feminist writers resisted the death of the author on the grounds that we didn’t want to get killed off before we existed.” 15 15 Moyes, Lianne, editor. “In Conversation: Gail Scott, Lianne Moyes and Corey Frost.” Gail Scott: Essays on Her Works, Guernica, 2002, p. 213. Consequently, instead of removing author subjectivity from their texts, these movements focus on challenging patriarchal and conventional narrative forms by foregrounding subjectivity in all its complexity. Permanent Revolution continues these discussions while taking into account the socio-historical developments that have occurred since the ‘70s and the current political landscape: the collection broadens its concept of gender and sexuality and considers the intersection of feminism and queerness with race, social class, and culture. Moreover, Scott views linguistic and gender inequalities within Canada through the larger scope of settler colonialism and Indigenous rights.

Scott also situates her book within the context of Canada’s unique linguistic situation. Permanent Revolution is an English text framed by the bilingual city of Montréal, where Scott lives and works as part of an Anglo-Québécois minority within a Franco-Québécois majority, which is itself a minority in Anglo-Canada. Rather than limiting the scope of the text, this specificity allows for a rich and multi-faceted look at Canada’s literary world. Scott also makes comparisons between Canada and the U.S., rooting the collection in a wider English-speaking North American context. Geographical setting is important, as Scott sees it as significant for both identity and writing, which she explains in her own words:

Vis-à-vis the Americans, I could not, among other things, distill the American genius for popular culture tropes into my work. As did Bob. Nor did I wish to. Russia was a Northern country, like Québec, + something about the late 20th left-leaning geopolitics — or perhaps just the extremes of climate—fit. It is in cumulative microcosmic ways that the facets of our solidarities are altered according to the place from which we speak. 16 16 Permanent Revolution. pp. 39–40.

Thèmes & Sujets

Identity

Scott speaks of identity, especially marginalized identity, as hybrid. That is to say, no one’s identity is singular. Everyone experiences some kind of doubleness or multiplicity. Speaking of her woman friends, Scott describes their simultaneous (and at times contradictory) roles as “mother, writer, militant, lover, friend.” 17 17 Permanent Revolution. p. 95. Identity is also unstable: individuals are constantly shifting between these roles as they move through their days. They acquire new roles and shed old roles as their contexts change. Scott’s “sutured subject» 18 18 See the glossary of this reader’s guide for an explanation of the writing subject/sutured subject. is an attempt to express this flux of identity in language, which contrarily tends to fix things into permanence. 19 19 See “Language & Translation.” The sutured subject allows minority subjects to be authentically expressed in literature, which is crucial: without this allowance, they run the risk of remaining misrepresented against the backdrop of a dominant culture.

Contradictorily, Scott and other New Narrative 20 20 See the glossary of this reader’s guide for an explanation of New Narrative. and fiction/théorie 21 21 See the glossary of this reader’s guide for an explanation of fiction/théorie. writers realized early on that “[p]olitical agency involved at least a provisionally stable identity.” 22 22 Glück, Robert. “Long Note on New Narrative.” Biting the Error: Writers Explore Narrative, edited by Mary Burger, et al., Coach House, 2004, p. 26. Despite their belief that no identity is truly stable, in order to be taken seriously, feminist and queer writers had to publicly present at least a tentatively fixed self. The sutured subject was also a response to this demand because it provided something unified to point toward, one voice that could house this belief in a shifting multiplicity. This is also the work that a word like “Fe-male” 23 23 See the glossary of this reader’s guide for an explanation of Fe-male. or a statement like Eileen Myles’ “I’m the gender of Eileen” 24 24 Cox, Ana Marie. “Eileen Miles Wants Men to Take a Hike.” The New York Times Magazine, 13 Jan. 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/17/magazine/eileen-myles-wants-men-to-take-a-hike.html. does: it provides an umbrella under which all the different layers of one’s identity can be included without being essentialist or reductive. This is one example of the kind of experimentation that Scott sees as key for minority writers, and it exemplifies how writing can be related to ongoing social issues.

Question 1: How might creating a new word to identify oneself be freeing or limiting? How might this act contribute to defining one’s identity, and is this act more for oneself or for others?

Question 2: What literary devices or stylistic choices does Scott employ to express the sutured subject?

Activity: Create a new word, image, or sound that captures two different (or conflicting) aspects of your identity. Explain your choices. When discussing with your classmates, consider the difficulties of trying to merge two separate elements into a single representation, and reflect on how minorities do this every day.

Language & Translation

Scott is suspicious of language: for example, she notes that the word feminine is a masculine noun in French (le féminin), which highlights the unreliability of language. 25 25 Permanent Revolution. p. 16. For Scott, language often hides inherent biases that can undermine attempts to challenge conventions and norms. Consequently, she suggests that “all language has to be seen as material to work on” 26 26 Permanent Revolution. p. 121. and that it cannot be taken at face value. Therefore, in exploring how to express minority subjects she also considers language, asking, “what would writing that was also a questioning of words + sentences in relation to each other do to the shape of a story or novel?” 27 27 Permanent Revolution. p. 99.

Scott sees language as intimately connected to culture and identity. 28 28 Permanent Revolution. p. 106. She includes multilingualism as a contributing factor to feelings of hybrid identity. Living in bilingual Montréal, she speaks of the experience of living in translation: the reality of having to constantly switch between languages depending on what the situation calls for. As an Anglo-Québécois writer, she also speaks of the difficulties of having mostly non-Québécois readers:

I did sense that people in English Canada often thought of me as having precisely the same culture as themselves. Their not sensing my efforts at translating within my own language to make my words, in part borrowed from another culture, understandable, ‘accessible’ to them even as I spoke, was frustrating. 29 29 Permanent Revolution. p. 108.

She therefore considers translation within a broader definition. 30 30 See the glossary of this reader’s guide for an explanation of Scott’s use of the word translation. In Scott’s understanding, translation happens not only across different languages—say, from English to French—but also within one language. Translation transmits meaning across cultures, social classes, and individuals, and it involves both the writer/speaker and the reader/listener:

Sometimes when I read criticism of my work coming from English Canada, I have to translate the criticism. By that I mean I have to guess where the critic is writing from, guess at its subtext coming from its community fabric, in order to understand it. Just as s/he had speculated, given the necessary loss of nuance, in reading. 31 31 Permanent Revolution. p. 111.

Question 1: What gets lost in translation? How can we try to mitigate such loss? Is this loss inevitable?

Question 2: Do you consider translation an act of violation or an act of paying homage? What might make translation feel appropriative? What might make it more respectful?

Activity: Play a game of telephone: The first person whispers a sentence into the second person’s ear. Repeat down the line. The last person says out loud what they heard. Compare what the last person says to the original sentence. Alternatively, play this game in writing. Consider what was lost or transformed during this exercise.

Style & Esthétique

Scott’s essays use a juxtapositional method. She places various texts—theoretical reflections, memories, narrated scenes, snippets of conversations, excerpts from her novels, quotes from other writers, segments from interviews, journal entries—side by side, creating more of a collage than a formal essay. She emphasizes this visually by creating breaks with ALL-CAPS headers, indenting whole paragraphs, and rendering long passages in italics. This method reflects her notion that “[t]he struggle for style is the struggle to find a rapport d’adresse that speaks in conflicted directions without loss.” 32 32 Scott, Gail. “The Porous Text, Or, The Ecology of the Small Subject: Take 2.” Chain, no. 5, 1998, p. 206. Juxtaposition allows conflicting, even contradictory sentiments to exist side by side in the text.

The effect of this method is that, instead of moving forward in a linear progression, the text meanders, spirals, returns upon itself, and shifts laterally between points. In turn, the reading experience is significantly slowed down, opening up space for readers to linger on the page, view topics from multiple perspectives, and be active participants. Instead of telling her audience what to think, Scott invites them to explore their own ideas, opinions, and conclusions. She further achieves this effect through other stylistic choices:

– use of neologisms, e.g., Fe-male, writing subject/sutured subject

33

33 See the glossary of this reader’s guide for an explanation of Fe-male and the writing subject/sutured subject.

– use of French-like words and spellings, e.g., unskirtable, based on the French word incontournable

– use of specialized language or jargon, e.g., bromides, vectors, fractal

– use of + as a conjunction instead of and

Such idiosyncrasies invite a different kind of interaction with the text, encouraging the reader to be active in their reading, as they revisit sentences multiple times. The text’s stylistic oddities also help the reader to distinguish particular words, moments, and ideas and create bridges across the text.

Scott’s juxtapositional method supports her idea that experimentation is crucial to the marginalized writer, whether they write novels or essays. For Scott, style is partially a by-product of trying to create a sutured subject. It is therefore intimately linked to identity and rooted in the artist’s responsibility to be a critic of their own culture and time. Scott states this in her own words:

From the point of view of identity, the writing subject, then, necessarily wavers. In time, this instability becomes style. To live in a context that fosters style is a phenomenal privilege.

34

34 “The Porous Text.” p. 203.

Ressources

More on Permanent Revolution

- “Gail Scott reads from Permanent Revolution!”

- A 10-minute YouTube video, uploaded by Librairie Drawn & Quarterly, in which Scott presents and reads from her book. A good way to hear the author in her own voice and get a feel for the rhythm of the text.

- Review of Permanent Revolution in Montreal Review of Books

- An insightful book review wherein writer H. Felix Chau Bradley shares a correspondence they had with Scott about Permanent Revolution. A good place to start if feeling overwhelmed by the text’s experimental form and language.

Texts to Read Alongside Permanent Revolution

- Robertson, Lisa. Nilling: Prose Essays on Noise, Pornography, The Codex, Melancholy, Lucretius, Folds, Cities and Related Aporias. Book*hug, 2012.

- During the virtual book launch of Permanent Revolution with Book*hug Press (here on YouTube) Scott mentions that Robertson’s Nilling was on her mind (and literally on her desk) while she was writing her book.

- Any of Gail Scott’s novels

- Scott discusses her own novels and writing techniques throughout Permanent Revolution. Though not a prerequisite, reading her novels provides an opportunity to experience her theory in practice.

Further Reading on New Narrative & fiction/théorie

- Glück, Robert. “Long Note on New Narrative.” Biting the Error: Writers Explore Narrative, edited by Mary Burger, et al., Coach House, 2004, pp. 25–34.

- A text on New Narrative written by one of its founders.

- Bersianik, Louky, et al. Theory, a Sunday. Translated by Erica Weitzman, et al., Belladonna*, 2013.

- A collection of essays written by the leading figures of fiction/théorie.

Glossaire

New Narrative

A queer literary movement originating in 1970s San Francisco. It is a response to avant-garde poetry movements (notably, Language Poetry) that advocate for rigorous formal and linguistic experimentation with the aim of eliminating the author and subjectivity from the text. New Narrative embraces this experimentation, applying it to prose, but directs it instead towards the inclusion and representation of queer and other marginalized subjects, who are often omitted or only represented stereotypically. 35 35 Burger, Mary, et al., editors. Biting the Error: Writers Explore Narrative. Coach House, 2004, pp. 25–34. Notable figures include Robert Glück, David Boone, Gail Scott, Dodie Bellamy, Kathy Acker, Kevin Killian, and Gary Indiana.

fiction/théorie

A literary genre created by feminists in 1980s Québec. It explores methods of female expression and écriture au féminin (writing in the feminine) that challenge traditional narratives and patriarchal representations of women in literature. Underpinned by the viewpoint of language as inextricably linked to social, political, and gender issues, it holds that challenging social conventions necessarily involves challenging language itself, thereby favouring experimental narrative and linguistic approaches in writing female subjects. 36 36 Bersianik, Louky, et al. Theory, a Sunday. Translated by Erica Weitzman, et al., Belladonna*, 2013. Notable figures include Gail Scott, France Théoret, Nicole Brossard, Louky Bersianik, Louise Cotnoir, and Louise Dupré.

Fe-male

A conceptual label coined by Scott used to identify herself. It is a response to complex questions about whether a lesbian is a woman, to which Scott’s answer is, “yes and no, or yes or no, in varying degrees.” 37 37 Chau Bradley, H. Felix. “Gathering Language: Permanent Revolution.” Montreal Review of Books, 21 July 2021, mtlreviewofbooks.ca/reviews/permanent-revolution. It reflects in written form what Scott refers to as her “fractured female being” 38 38 Permanent Revolution. p. 95. and the impossibility of creating “unary female characters” 39 39 Permanent Revolution. p. 96. . The splitting of the word into two distinct syllables (Fe- and -male) points to simultaneously being a part of and apart from conventional conceptual gender categories. 40 40 Permanent Revolution. p. 27.

writing subject/sutured subject

Scott’s conceptual label for the voice that speaks in and out of experimental narratives. More than just the author, a narrator, or a character or persona, it is a blurring and blending of these traditional narrative roles that requires the reader to fill in gaps and participate in its creation. It is an attempt to represent in prose the unstable and hybrid nature of identity, and it includes the implicit historical, social, geographical, and other contextual elements that help shape said identity. 41 41 Permanent Revolution. p. 41. The sutured subject is, therefore, not singular but made up of layers of different voices, textures, times, and places spliced together, hence the word sutured. 42 42 Permanent Revolution. p. 62.

translation

Conventionally defined as “the action of converting from one language to another” 43 43 “Translation.” Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, 2019, www.oed.com/dictionary/translation_n. and “the action of transferring or moving a person or thing from one place, position, etc., to another,” 44 44 “Translation.” Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, 2019, www.oed.com/dictionary/translation_n. Scott uses the word with an extended meaning to discuss how a person’s identity—shaped through unique experiences and contexts—affects their language. In this sense, translation also occurs within one language, with “words sitting differently in language” 45 45 Permanent Revolution. p. 55. depending on who is speaking (and who is hearing). For Scott, to translate means to interpret a speaker’s language while taking into account their context (as well as one’s own) and considering how this context might affect meaning. 46 46 Permanent Revolution. p. 111. Thus, translation is not only transmission across languages and spaces but also across cultures, histories, social classes, and individuals.

Crédits

L’Espace de la diversité recognizes the generous support of the Canada Council, the Conseil des arts et des lettres du Québec, the Conseil des arts de Montréal, and the Fondation Lucie et André Chagnon.

- Coordination: Emma Telaro

- Research and Writing: Shannon Campbell

- Editing: Danielle Carter

Espace de la diversité

1260, rue Bélanger, Suite 201

Montréal, Québec, H2S 1H9

Phone: 438-383-2433

- 1 Scott, Gail. Permanent Revolution. Book*hug, 2021, p. 5.

- 2 Permanent Revolution. p. 60.

- 3 Permanent Revolution. pp. 95–96.

- 4 Scott, Gail. Heroine. Coach House, 1987.

- 5 Scott, Gail. Main Brides: Against Ochre Pediment and Aztec Sky. Coach House, 1993

- 6 Scott, Gail. My Paris: A Novel. Mercury, 1999.

- 7 Scott, Gail. The Obituary. Coach House, 2010.

- 8 Delisle, Michael. The Sailor’s Disquiet. Translated by Gail Scott, Mercury, 2000.

- 9 Bersianik, Louky, et al. La théorie, un dimanche. Les Éditions du remue-ménage, 1988.

- 10 Burger, Mary, et al., editors. Biting the Error: Writers Explore Narrative. Coach House, 2004.

- 11 Moyes, Lianne, editor. “Brief Biography of Gail Scott.” Gail Scott: Essays on Her Works, Guernica, 2002, pp. 231–234.

- 12 See the “Style & Aesthetics” section of this reader’s guide for more on Scott’s writing style.

- 13 See the glossary of this reader’s guide for an explanation of New Narrative.

- 14 See the glossary of this reader’s guide for an explanation of fiction/théorie.

- 15 Moyes, Lianne, editor. “In Conversation: Gail Scott, Lianne Moyes and Corey Frost.” Gail Scott: Essays on Her Works, Guernica, 2002, p. 213.

- 16 Permanent Revolution. pp. 39–40.

- 17 Permanent Revolution. p. 95.

- 18 See the glossary of this reader’s guide for an explanation of the writing subject/sutured subject.

- 19 See “Language & Translation.”

- 20 See the glossary of this reader’s guide for an explanation of New Narrative.

- 21 See the glossary of this reader’s guide for an explanation of fiction/théorie.

- 22 Glück, Robert. “Long Note on New Narrative.” Biting the Error: Writers Explore Narrative, edited by Mary Burger, et al., Coach House, 2004, p. 26.

- 23 See the glossary of this reader’s guide for an explanation of Fe-male.

- 24 Cox, Ana Marie. “Eileen Miles Wants Men to Take a Hike.” The New York Times Magazine, 13 Jan. 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/17/magazine/eileen-myles-wants-men-to-take-a-hike.html.

- 25 Permanent Revolution. p. 16.

- 26 Permanent Revolution. p. 121.

- 27 Permanent Revolution. p. 99.

- 28 Permanent Revolution. p. 106.

- 29 Permanent Revolution. p. 108.

- 30 See the glossary of this reader’s guide for an explanation of Scott’s use of the word translation.

- 31 Permanent Revolution. p. 111.

- 32 Scott, Gail. “The Porous Text, Or, The Ecology of the Small Subject: Take 2.” Chain, no. 5, 1998, p. 206.

- 33 See the glossary of this reader’s guide for an explanation of Fe-male and the writing subject/sutured subject.

- 34 “The Porous Text.” p. 203.

- 35 Burger, Mary, et al., editors. Biting the Error: Writers Explore Narrative. Coach House, 2004, pp. 25–34.

- 36 Bersianik, Louky, et al. Theory, a Sunday. Translated by Erica Weitzman, et al., Belladonna*, 2013.

- 37 Chau Bradley, H. Felix. “Gathering Language: Permanent Revolution.” Montreal Review of Books, 21 July 2021, mtlreviewofbooks.ca/reviews/permanent-revolution.

- 38 Permanent Revolution. p. 95.

- 39 Permanent Revolution. p. 96.

- 40 Permanent Revolution. p. 27.

- 41 Permanent Revolution. p. 41.

- 42 Permanent Revolution. p. 62.

- 43 “Translation.” Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, 2019, www.oed.com/dictionary/translation_n.

- 44 “Translation.” Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, 2019, www.oed.com/dictionary/translation_n.

- 45 Permanent Revolution. p. 55.

- 46 Permanent Revolution. p. 111.