Mots-clés

Publication

Extrait

Our fractured pupils and dilated jaws become the moon when it blocks out the sun, hailstorms, magic disguised as nightmares. Clammy synth pop disperses across my skin like bubbling fizz candies. I bounce around in the passenger seat, smoking cigarettes with the window down. When we reach the legislature grounds, the sun is rising.

Standing in a shallow pool, dark electric clouds sway into the pink of sunrise. They form a circle, leaving the piece of sky above me untouched.

A hole.

An awful beauty that haunts, that speaks to me.

The whole world sits in the sky and the world is ending. Pink clouds swirl into funnels. Twirling pink fingers try to reach the eart.

quasi-stars penetrate the “indian” that i was sky evolves

into an inviting shadow allow light to enter the third eye,

brightening holistic phantom of her words denesuline:

“the real people” i don’t like thinking about the doubling

of shadows as midnight approaches

the light bares healing stories.

moving out of slum indigo

1

1 Purcell, Kaitlyn. ʔbédayine, Metatron, 2019.

(p. 29–30)

Thana jumps and laughs. She pulls me in and kisses me. Her beauty vibrates through my lips, through my body. The insides of my skin crawl in a bed made out of the softest moss and flower petals. This is where the fairies live.

Love

wonder when i’ll see her again

i’ve been grieving my sobriety

forgot to smudge today

and for the last twenty years

wishing for the smell

of incense and candles

i can feel my heart

everywhere.

everywhere.

Thana pulls her lips away with a warm sigh, and we look out across the river. I nuzzle my head into hers. (p. 79–81)

Biographie

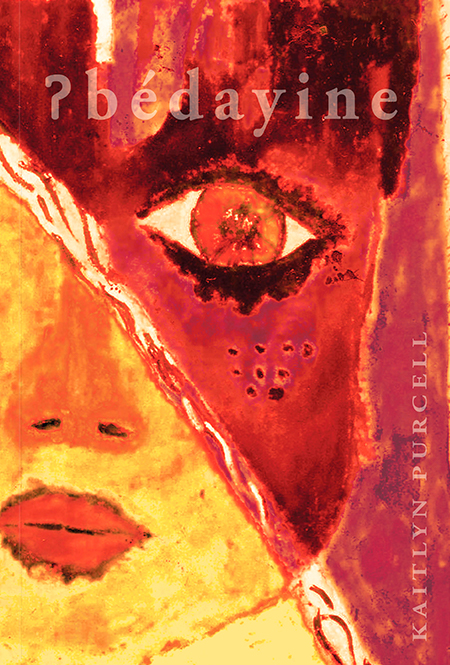

Kaitlyn Purcell is an artist, poet, storyteller, and scholar who works in multimodal creative productions that include visual, digital, and installation arts. She is Denesuline-Irish and a member of Smith’s Landing First Nation (Treaty 8 territory). She is an SSHRC-funded PhD candidate at the University of Calgary, where she studies Indigenous literatures, creative writing, and community-based learning. ʔbédayine, published in 2019 by Metatron Press, is her first book. Its stories are partly inspired by Purcell’s own experiences as a young woman in Edmonton, during a time as an adolescent when she was detached from her Dene roots. For her poetic novella ʔbédayine, Purcell was nominated for a 2020 Indigenous Voices Award and was selected, by guest judges CAConrad and Anne Boyer, for the 2018 Metatron Prize for Rising Authors. Her writing can be found in venues such as Artspeak, Esker Foundation, and YYZ Artists’ Outlet.

Résumé

ʔbédayine is a poetic novella that tells the story of Ronnie, a young Indigenous woman who experiences love, addiction, trauma, and healing in the city of Edmonton, Alberta. The story begins with Ronnie and her friend Thana leaving their small community of Fort Smith in the Northwest Territories. In Edmonton, they rent a small apartment and procure jobs in clothing shops, movie theatres, and bars. The city is a source of both pain and pleasure for Ronnie. She becomes addicted to drugs and loses control. Thana tries to help Ronnie beat the addiction and becomes indispensable to the otherwise solitary young woman.

Eventually, Ronnie meets a series of young men with whom she falls in love. These relationships end abruptly, and Ronnie feels lost. Thana begins taking care of Ronnie once again. They continue to drink, get high, and attend parties. After one particularly disastrous night, Ronnie is left alone on the side of the highway and thinks to herself, “Why do I keep doing this to myself? Why does nobody care?” (p. 93) In the end, the story does not resolve the problems facing these two young women, but it does hold the promise of future healing.

Situer l’œuvre

Purcell is one of several Indigenous writers creating some of the most exciting and innovative work across Turtle Island and Canada today. ʔbédayine enters a tradition of genre-crossing work that includes Anishinaabe writer, scholar, and artist Leanne Betasamosake Simpson’s collections of stories and songs and experimental novel (Islands of Decolonial Love, 2015; This Accident of Being Lost, 2017; and Noopiming: The Cure For White Ladies, 2020); Nisga’a poet and scholar Jordan Abel’s visual poetry, sound performances, and autobiographical writing (NISHGA, 2021; Injun, 2016; and The Place of Scraps, 2013); and Cree writer and academic Billy-Ray Belcourt’s autofiction and poetry (A Minor Chorus: A Novel, 2022; A History of My Brief Body, 2020; and NDN Coping Mechanisms: Notes from the Field, 2019). This new work is indebted to earlier waves of Indigenous writers, who first secured a voice for First Nations, Métis, and Inuit literature in Canadian publishing. This earlier generation includes Lee Maracle (Stó:lō author of Bobbi Lee: Indian Rebel, 2017) 2 2 Maracle, Lee. Bobbi Lee: Indian Rebel. Women’s Press, 2017, 210 pages. , Tomson Highway (Cree playwright of The Rez Sisters, 1992) 3 3 Highway, Tomson. The Rez Sisters. Fifth House, 1992, 132 pages. , Maria Campbell (Métis author of Halfbreed, 2019) 4 4 Campbell, Maria. Halfbreed. Penguin, 2019, 224 pages. , and Markoosie Patsauq (Inuk author of Hunter with Harpoon, 2020). 5 5 Patsauq, Markoosie. Hunter with Harpoon. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2020, 104 pages.

Many of these Indigenous writers are known for producing cross-genre works, which do not sit neatly in Eurocentric categories for literature: fiction and non-fiction; prose and poetry; or realism and fantasy. In Why Indigenous Literatures Matter, Cherokee scholar and writer Daniel Heath Justice introduces the term “wonderwork” as an alternative to this binary mode of reading and writing literature: “These terms and concepts are burdened by dualistic presumptions of real and unreal that don’t take seriously or leave legitimate space for other meaningful ways of experiencing this and other worlds—through lived encounter and engagement, through ceremony and ritual, through dream.” 6 6 Justice, Daniel Heath. Why Indigenous Literatures Matter. Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2018. (p. 152) In ʔbédayine, along with interweaving poetry and prose, Purcell regularly introduces dream episodes within the realistic representations of young Indigenous life. See, for instance, “Highway of Tears,” which introduces the key plot point of the end of Ronnie and Steve’s relationship through a dream. Thana listens attentively as Ronnie describes her dream about failing to properly place a bait fish on a hook. Matty, Thana’s boyfriend, is in the car with them and responds, “That’s some crazy metaphorical shit.” 7 7 Purcell, Kaitlyn. ʔbédayine. Metatron, 2019, 106 pages. (p. 90) Significantly, however, dreams are never simply metaphors in Purcell’s writing. Similar dream episodes occur in the cross-genre writing, or “wonderworks,” of Oji-Cree writer Joshua Whitehead (Jonny Appleseed) 8 8 Whitehead, Joshua. Jonny Appleseed. Arsenal Pulp Press, 2018, 224 pages. and Inuk writer Tanya Tagaq (Split Tooth). 9 9 Tagaq, Tanya. Split Tooth. Penguin, 2019, 208 pages.

Thèmes et sujets

Indigenous Identity

ʔbédayine explores Indigenous identity through representing the ways in which the poetic novellas’ protagonist, Ronnie, has become disconnected from her First Nations roots. Purcell, who is Denesuline-Irish, depicts the rural community of Fort Smith, Northwest Territories as home to Dene, Métis, and Dogrib nations in the prose poem of the same name (“Fort Smith”) that opens the book. Once Ronnie and her friend Thana are in Edmonton, the Denesuline nation is referenced just one more time in a poetic interlude in the short story “Wanderrotten”: “denesuline: / ‘the real people’” (p. 30).

At other points in the poetic novella, Indigenous identity becomes a possible point of connection between Ronnie and others; for instance, her first boyfriend in the city “looks like a mixture of white and native” (p. 24). Ronnie’s relationship with Jake, however, is short-lived and rife with drug abuse and emotional difficulty. The next “native” (p. 55) characters who appear are the titular sisters in the short story “Sisters,” but their appearance precedes a brutal physical assault on Ronnie: “I don’t understand. Why do they want to hurt a cousin, a sister?” (p. 55) The final Indigenous character to appear in the poetic novella is the “tall native guy” who was involved in another brutal assault; this time, the victim is Ronnie’s friend Joey. While Joey is receiving medical attention for his life-threatening wounds, Ronnie sees “the could-be-beautiful native guy” (p. 61) sitting in the back seat of a bus. The story ends as Ronnie points her finger at the assailant and tells the drivers, “That’s one of them. The ones who did it.” (p. 61) In these examples, Ronnie’s First Nations identity is not a source of connection but confusion. Separated from her Dene roots, the protagonist finds herself lost in a city where such connective tissue leads not to community but to violence.

Questions

- What forces may have caused the disconnection between Ronnie and her Dene roots? Consider the role of the city, drug use, and isolation from family and friends as you answer this question.

- The title, ʔbédayine, is Denesuline for “its spirit.” Can you locate moments in the book when Dene spirit appears present, even if the character remains disconnected from her First Nations roots?

Activity

The author and her protagonist are both Dene. Using trusted research tools (e.g., The Canadian Encyclopedia), prepare a brief fact sheet about this First Nations community that briefly describes their history pre-colonization; their ongoing survivance post-colonization; and their language and storytelling traditions.

Gendered Violence

ʔbédayine also explores gender identity, through representation of a young woman and her experience with love, sex, and violence in the city of Edmonton, Alberta. This theme is multifaceted, for Ronnie’s traumatic experiences speak to the power imbalance between men and women while they also foreground the role substance abuse (i.e., alcohol and drugs) plays in the ongoing cycle of trauma. Dangerously disconnected from herself, Ronnie is frequently exposed to new and dangerous situations.

Even Ronnie’s positive relationships with men are overwritten by violence. When Ronnie first visits her boyfriend Jake’s apartment, her first thought is “I wonder if I’m going to die tonight.” (p. 38) In the following poetic interlude that reveals the dissolution of their relationship, it is apparent that these two were not on equal terms: “he falls in love for an hour and I / fall in love for a month” (p. 41). In “Love Is,” Ronnie wanders the city selling drugs with her new boyfriend Steve. As she documents the kinds of people they encounter, we see the young women, each one suffering from addiction, reduced to sexual objects: “Only pretty girls wither away. These boys love to see my bones, and they love the legs-open lullaby. I sing better when I’m high.” (p. 47)

The book’s penultimate story represents a Ronnie more disconnected from her body than ever before. Throughout the story, Ronnie repeatedly thinks, “My body is nothing” (p. 93), and, “I need to put my body back where it belongs.” (p. 94) Fortunately, Ronnie is reunited with her friend Thana and, together, they drive back to their new home in Edmonton, Alberta. Thana puts a stop to a final experience of sexual harassment and Ronnie replays this rare moment of what feels like justice: “Each time with a new face.” (p. 98) Thus, as the poetic novella ends, the many individual instances of violence experienced by Ronnie become an amalgamation of gendered trauma that, replayed in the company of a friend, can be transformed into healing.

Questions

- What are some of the common descriptions Purcell uses in her work to identify girls or women and boys or men? How does the language she uses contribute to our understanding and questioning of gender roles, violence, and identity?

- Purcell’s book also features positive relationships. Can you find an example of one such relationship? Discuss how and why this relationship, or this one moment in the relationship, has overcome the book’s tendency to slip into violence.

Activity

Identify a poetic interlude in the text that appears to represent an experience of substance abuse or gendered violence. What other means can you use to represent Ronnie’s experience? Create a visual collage, using print or electronic media, inspired by the poem’s word choice, imagery, and/or metaphors.

Style et esthétique

Purcell’s book is a poetic novella. This means that the book is a work of fiction slightly shorter than a typical novel, mixing prose with elements typical of poetry, including experimental form, heightened imagery, and figures of speech. As a novella, the book reads as one coherent story; however, due to the individual titles of each part or chapter, it is also possible to read the book as a short story cycle. In a short story cycle, the individual parts can stand on their own but also bear an undeniable relationship to one another on the basis of character, place, time, or theme. The short story cycle is common in Canadian literature; examples include the well-known Lives of Girls and Women by Alice Munro

10

10 Munro, Alice. Lives of Girls and Women., Penguin, 2021, 248 pages.

and the more recent Dominoes at the Crossroads by Kaie Kellough.

11

11 Kellough, Kaie. Dominoes at the Crossroads. Véhicule Press, 2020, 180 pages.

The first part of the book is titled “Fort Smith.” This is a one-page prose poem, that is, a poem written using the tonal, stylistic, or formal techniques of prose. In this case, the prose poem form is evident due to the absence of line breaks. Following a short story, a second prose poem titled “Edmonton” appears. These are the only two individually titled poems in the book. It is notable that both prose poems concern place: the rural town in the Northwest Territories that Ronnie and Thana leave and the city in Alberta in which they begin their new lives, respectively. Both poems also represent the difficulty of the lives of Indigenous Peoples and other individuals minoritized or marginalized due to class, ethnicity, and/or race.

Though no other individually titled poems appear in the book, poetry remains a key component in the remainder of the poetic novella. For instance, when Ronnie is intoxicated, the fiction’s prose ruptures and suddenly transforms into poetry, distinguished stylistically by its use of italics. Lines of poetry appear in “Falling” after Ronnie swallows her first ecstasy pills. Simile (“17 years sings like broken / sunglasses”), repetition (“jaw clenching,” “jaw clenching”), and white space are clear markers of poetic form and style. Here and elsewhere, poetry takes over when the experience eludes realistic description. In other instances, poetry takes over when the experience is especially violent or traumatic: after Ronnie is physically assaulted by another Indigenous young woman in “Sisters,” a poetic interlude follows the story on page 57. The interlude includes the personification and anthropomorphization of natural forces (e.g., tornado and smoke) and the use of metaphor (e.g., the solar system becomes “a six-pack of tall cans”) to present a speaker who is trying to make sense of senseless violence.

Ressources

“Geopoetics.” Future Ecologies, season 4, episode 10, 25 Feb. 2023, futureecologies.net/listen/fe-4-10-geopoetics.

This podcast episode serves as an introduction to a theme pertinent to Purcell’s work in ʔbédayine and elsewhere: ecology, environment, and climate crisis.

McGregor, Hannah, et. al., editors. Refuse: CanLit in Ruins. Book*hug Press, 2018.

This collection includes contributions from Tuscarora (Six Nations of the Grand River) writer Alicia Elliott, Métis writer Chelsea Vowel (also the author of Indigenous Writes: A Guide to First Nations, Métis, & Inuit Issues in Canada), and Oji-Cree (Peguis First Nation) writer Joshua Whitehead.

Paige, Abby. Review of ʔbédayine by Kaitlyn Purcell, Swelles by Sina Queyras, and Vulgar Mechanics by K. B. Thors. Montreal Review of Books, 20 March 2020, mtlreviewofbooks.ca/reviews/poetry-17.

This review is an excellent way to introduce readers to the role of local literary magazines in the conversation about diverse literature.

Printup, Branden, host. “An Indigenous Woman’s Story of Losing and Learning.” Indie Book Review, 12 Sept. 2020, podcasters.spotify.com/pod/show/indiebookreview/episodes/An-Indigenous-Womans-Story-of-Losing-and-Learning-ehrgrb.

This short podcast episode is a useful model for how to produce a personal response to a literary text in a way that falls outside the conventional medium of the written essay.

Younging, Gregory. Elements of Indigenous Style: A Guide for Writing By and About Indigenous Peoples. Brush Education, 2018, 168 pages.

This invaluable resource includes a history of Indigenous representation in literature, an overview of the cultural rights of Indigenous Peoples, and instruction for the appropriate terminology to use when discussing First Nations, Métis, and Inuit communities.

Glossaire

Indian

Ronnie uses this word to describe herself in two separate prose poems. The word appears in quotation marks, which may suggest this term has been used against her as an insult. Though the term “Indian” is still used in legal contexts by the Canadian government, it is not an appropriate term to use to identify First Nations in other contexts. Chelsea Vowel explains, “Many people agree that the term ‘Indian’ is a somewhat outdated and inappropriate descriptor and have adopted the presently more common ‘First Nations.’” 12 12 Vowel, Chelsea. “Got Status? Indian Status in Canada, Sort of Explained.” âpihtawikosisân, 14 Dec. 2011, apihtawikosisan.com/2011/12/got-status-indian-status-in-canada-sort-of-explained.

Native

Purcell’s protagonist uses this word several times throughout the text to identify other Indigenous characters. While this term was once common and, like the term “Indian,” continues to be used positively by in-group members, it is no longer considered appropriate for use by non-Indigenous peoples. It is preferable, whenever possible, to use the terms Indigenous, First Nations, Métis, or Inuit. See Gregory Younging’s Elements of Indigenous Style: A Guide for Writing by and About Indigenous Peoples for more information. 13 13 Younging, Gregory. Elements of Indigenous Style: A Guide for Writing By and About Indigenous Peoples., Brush Education, 2018, 168 pages.

Residential schools

The book’s opening prose poem, “Fort Smith,” describes the neglected state of the small town and the Indigenous Peoples who live there: “no / running water and no paint on their houses and children / pushed into residential schools” (p. 11). 14 14 Purcell, Kaitlyn. ʔbédayine. Metatron, 201 Naomi Angel describes the Indian Residential School (IRS) system in the following way:

Run by the government of Canada and the Presbyterian, Anglican, United, and Catholic churches, the system was in place for more than a century (1876–1996). It separated Indigenous children from their families and placed them in 139 recognized Indian residential schools across the country … The IRS system is now recognized as one of the major factors in the attempted destruction of Indigenous cultures, languages, and communities in Canada. 15 15 Angel, Naomi. Fragments of Truth: Residential Schools and the Challenge of Reconciliation in Canada. Edited by Jamie Berthe and Dylan Robinson, Duke University Press, 2022. (p. 1–2)

Crédits

L’Espace de la diversité recognizes the generous support of the Canada Council, the Conseil des arts et des lettres du Québec, the Conseil des arts de Montréal, and the Fondation Lucie et André Chagnon.

- Supervision: Selma Guessous

- Coordination: Emma Telaro

- Research and Writing: Jessi MacEachern

- Editing: Danielle Carter

- Graphic Design: Alejandra Núñez

Espace de la diversité

1260, rue Bélanger, Suite 201

Montréal, Québec, H2S 1H9

Phone: 438-383-2433

- 1 Purcell, Kaitlyn. ʔbédayine, Metatron, 2019.

- 2 Maracle, Lee. Bobbi Lee: Indian Rebel. Women’s Press, 2017, 210 pages.

- 3 Highway, Tomson. The Rez Sisters. Fifth House, 1992, 132 pages.

- 4 Campbell, Maria. Halfbreed. Penguin, 2019, 224 pages.

- 5 Patsauq, Markoosie. Hunter with Harpoon. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2020, 104 pages.

- 6 Justice, Daniel Heath. Why Indigenous Literatures Matter. Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2018.

- 7 Purcell, Kaitlyn. ʔbédayine. Metatron, 2019, 106 pages.

- 8 Whitehead, Joshua. Jonny Appleseed. Arsenal Pulp Press, 2018, 224 pages.

- 9 Tagaq, Tanya. Split Tooth. Penguin, 2019, 208 pages.

- 10 Munro, Alice. Lives of Girls and Women.

,Penguin, 2021, 248 pages. - 11 Kellough, Kaie. Dominoes at the Crossroads. Véhicule Press, 2020, 180 pages.

- 12 Vowel, Chelsea. “Got Status? Indian Status in Canada, Sort of Explained.” âpihtawikosisân, 14 Dec. 2011, apihtawikosisan.com/2011/12/got-status-indian-status-in-canada-sort-of-explained.

- 13 Younging, Gregory. Elements of Indigenous Style: A Guide for Writing By and About Indigenous Peoples., Brush Education, 2018, 168 pages.

- 14 Purcell, Kaitlyn. ʔbédayine. Metatron, 201

- 15 Angel, Naomi. Fragments of Truth: Residential Schools and the Challenge of Reconciliation in Canada. Edited by Jamie Berthe and Dylan Robinson, Duke University Press, 2022.